Once upon a time, back in the late 1480s, when the founder of the Sikh religion Baba Guru Nanak was in his teenage years, his father Mehta Kalu gave him twenty rupees and asked him to go buy goods from another village and sell them for profit. Baba Guru Nanak left home. On the way, he came across a village where locals were starving. Instead of doing business he bought food supplies and fed the hungry people for free. This was the beginning of the “Guru ka Langar!” tradition. Those twenty rupees invested by Guru Nanak almost over five hundred years ago continue to feed hungry people all over the world.

Langar is a community kitchen, where food is shared with all visitors regardless of their religion, caste and creed. The food is cooked and served by volunteers. The spirit of Langar demands that the food should be served in a community gathering (Sangat) where everyone is treated equal and it doesn’t matter who is serving and who is eating.

Late October this year, when I couldn’t continue my journey up north due to the cold weather and had to change the route I ended up being in Surrey, BC where I was hosted by Mr Shahab Tangwani. He is from Kot Addu, a village only 17 km from my hometown Layyah in Pakistan, and is also Saraiki-speaking like me. Knowing my interest in cultures and traditions, he asked if I wanted to have Langar at Guru Nanak Gurdwara. I immediately said yes.

Guru Nanak Gurdwara serves Langar to thousands of people every day between 6 AM and 9 PM. It is mandatory to cover your head and remove shoes before entering Langar Hall. Men, women, and children sit together in rows (Pangat) on the floor and eat. Dozens of Sikh community members volunteer their service in the kitchen by cooking, serving and cleaning dishes with great enthusiasm. This kind of spirit is missing from the Langars at mosques, Darbaars or religious festivals in Pakistan where people make payments for food which is then cooked by professionals and then distributed by some other people.

While having Langar, I noticed that elderly people are washing dishes and mopping the floor whereas younger people are sitting and eating respectfully. Sewa (selfless service) without expecting a reward is an important aspect of Sikhism.

An elder told me a story from the area.

A thief was caught in a theft. The court judge asked him, “why were you stealing?”

“So I could buy some food and feed myself!” thief replied.

“Why would you steal when you have a Gurdwara nearby which serves free food to everyone?”

It is true that no one can die of hunger in the vicinity of a Gurdwara.

The food served in the Langar is vegetarian, to ensure that everyone, whichever faith they belong to, can eat. It consists of lentils, vegetable soup, roti, rice, raita (yoghurt), salad, and sweets. It is made of organic ingredients and is moderately spiced to suit everyone’s taste. Langar must be cooked freshly, without mixing it with leftovers, and in the same way as one would cook for their own family. The raw material for the food must be contributed by an honest living.

It was my first visit to a Gurdwara. I was not sure if I would be welcomed at all, but I was amazed at the openness and friendliness of Sikhs. When I asked them hesitantly if I could take their pictures, they would say, “Khich lo, khich lo (take it, take it)”. While I would be clicking pictures, they would be softly reciting, “Waheguru, Waheguru!” referring to God. I was invited into the kitchen where I saw a dozen women diligently making roti and a young man frying Jaleebi.

During my one week stay in Surrey, I went to Guru Nanak Gurdwara four times to document the Langar story.

No one looked at me as if I was an outsider. Everywhere I went in the Gurdwara, I was greeted with a smile. Despite knowing that Shahab and I were not Sikhs, no one tried to preach to us.

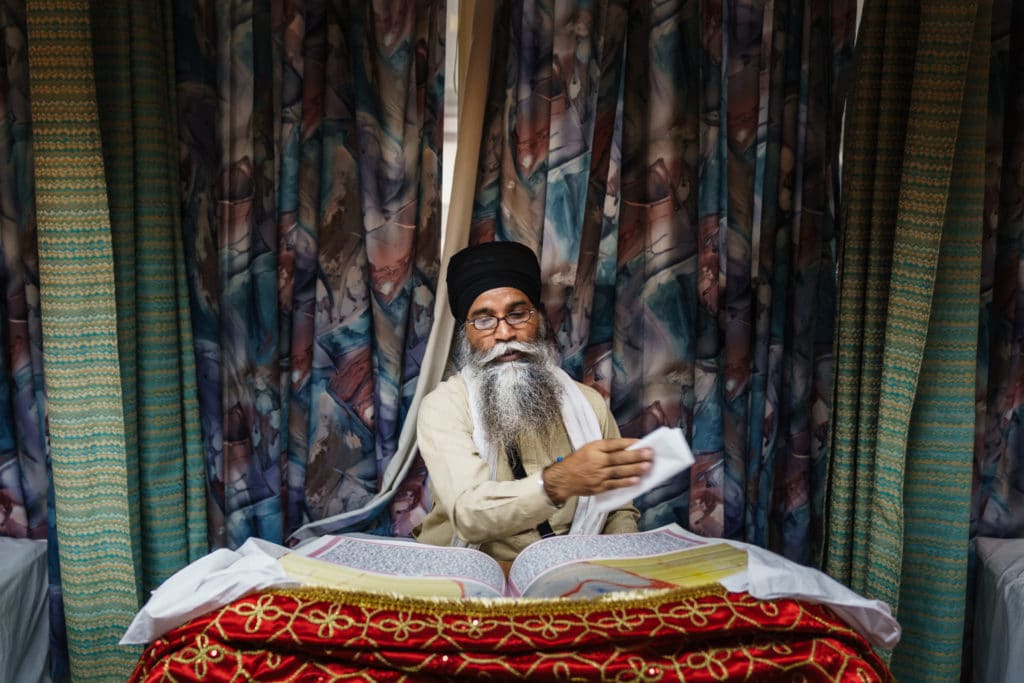

In the Diwan Hall (prayer hall), Sikhs bowed before Guru Granth Sahib, a compilation of hymns and prayers, which they regard as the 11th and eternal Guru in Sikhism. A devotee stood and waved Chaur Sahib, a fan constructed from yak hairs, above the Granth Sahib to show reverence and dedication. Guru Granth Sahib contains not only the revelations of the Sikh Gurus, but also of Muslim and Hindu Saints, and is a living example of interfaith harmony. It instructs its followers to respect all religious scriptures, the Bible, the Torah, the Holy Quran, the Vedas, and others.

An elder delivered a sermon in Punjabi language and talked about the history, the teachings of Gurus and the sacrifices they made, and how to be a good human, with no mention of heaven and hell. In between the sermon, Ragis (musician) sang hymns on musical instruments. The Ragis had come from India to perform Kirtan in Gurdwaras across Canada.

At the entrance of Diwan Hall, I sat down with a Babaji and asked him what it means to be a Sikh. He said:

“The word Sikh means “disciple”. You cannot be a Sikh if you cannot kill your ego. Humility is the key part of Sikh religion. First, kill your ego if you want to learn. Baba Guru Nanak asked us to pray to God (Naam Japna), and earn honestly through hard work (Kirt Karna), and Vand Chakna, means to share and consume together! In Sikhism, God is the universal truth.”

“How do I know I have reached the truth?” I asked Babaji.

“You don’t need to be told. You will know when you have arrived.”

Outside, where devotees take off their shoes before entering the Langar Hall, I saw a young man voluntarily cleaning shoes of Sangat and putting them in order. Humility is an important aspect of Sikhism. Selfless service is a way for them to become humble.

“How can pride and humility coexist in a person? Aren’t they opposite?” I asked Babaji. He looked at me with a smile and said:

“A Sikh is proud of being humble—taking pride in not being dependent on others, working hard, as well as being brave and fighting against injustice, and—embracing humility to not consider oneself more important than others and to treat everyone with the utmost respect!”

On the way back from Gurdwara Sahib, my host pointed to a group of Sikh elders playing cards by the road. I immediately asked him to stop and turn around. It looked like a typical scene from a village in Punjab where one would see elders casually hanging out with each other after a day of hard work. After greeting them with “Sat Sri Akal” I asked what game they were playing. “Dewar bhabi!” came the reply. I didn’t know this game, so someone explained it to me. When they came to know that I am from Pakistan, they expressed their desire to come to Punjab, Pakistan so they could visit the site where their first Guru, Baba Guru Nanak, was born and spent his last years.

“Punjab on both sides of Pakistan-India border is the same. The British divided us!” they said.

After learning about my bicycle journey, an elder handed me 5 dollars, and another elder, 10 dollars. I tried to politely refuse, but they insisted I should take them.

“Puttar, waddeyaan day tohfay tu inkaar nahi kari da! (Son, you shouldn’t refuse the gift from the elders).”

I graciously accepted their gifts. While I was talking to them, I noticed another Sikh elder stopped by and listened to our conversation. After a few minutes, he came to me and said, “what are you doing here among these people? You know inside your heart that your destiny (manzil) is somewhere else!”

I nodded.

“Do you understand me?” he asked me.

“I am trying!”

“Come with me,” he took me aside and said in Punjabi, “toon ithay ki lay reya wein? Aye saray aqal de annay ne! Toon Allah naal siddhi line mila! Mein pichlay janam wich musalmaan si, tay is janam wich sikh, bus hor ziyada mein nahi das sakda tennu!”

translating to:

“What are you doing among these people who have no wisdom? Make a direct connection to Allah. I was a Muslim in my previous incarnation, now I am a Sikh. I cannot tell you more.

“I would have given you this,” signally towards what appeared to be a mala beads in his left hand, “but neither you are a Sikh, nor do you need it!”

He took my right hand in his right hand and looked deep into my eyes as if penetrating into my soul. There was a moment of silence between us. Suddenly, a thick fog began to surround us and we both disappeared into the mystical world.